main takeaway

Why do people accept (unfair) outcome inequalities if they reject inequality of opportunity ?

No need to assume limited awareness of unfairness

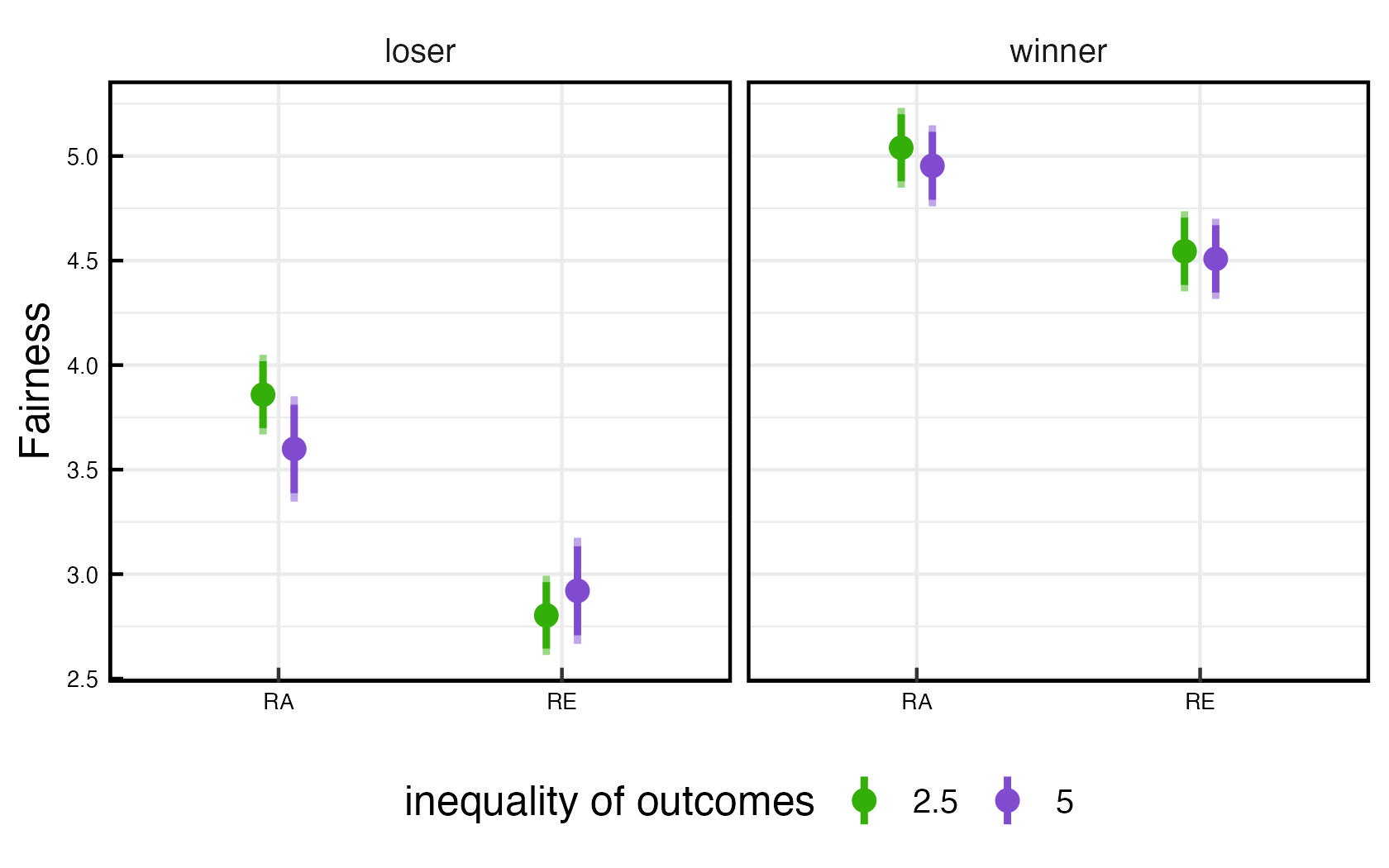

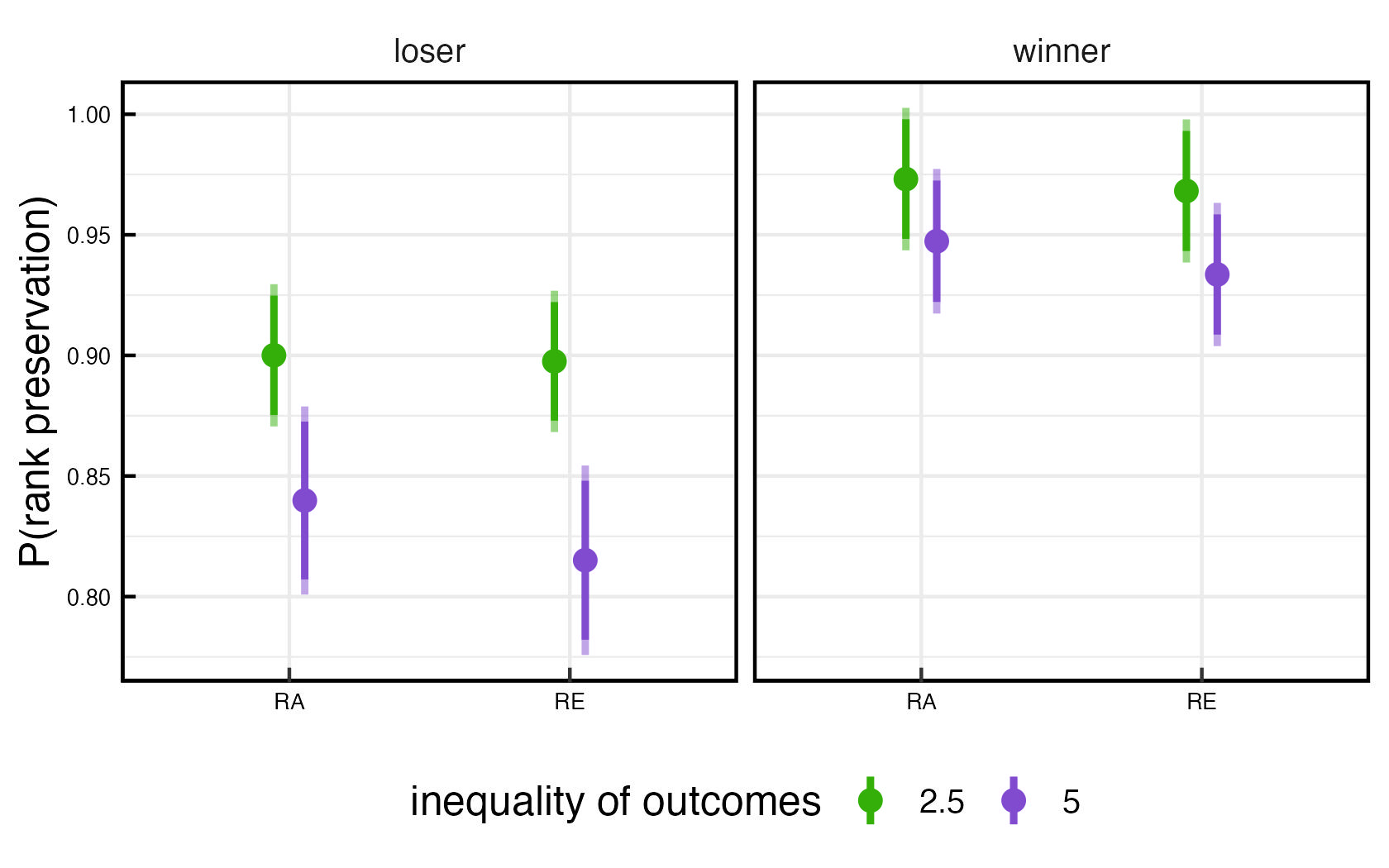

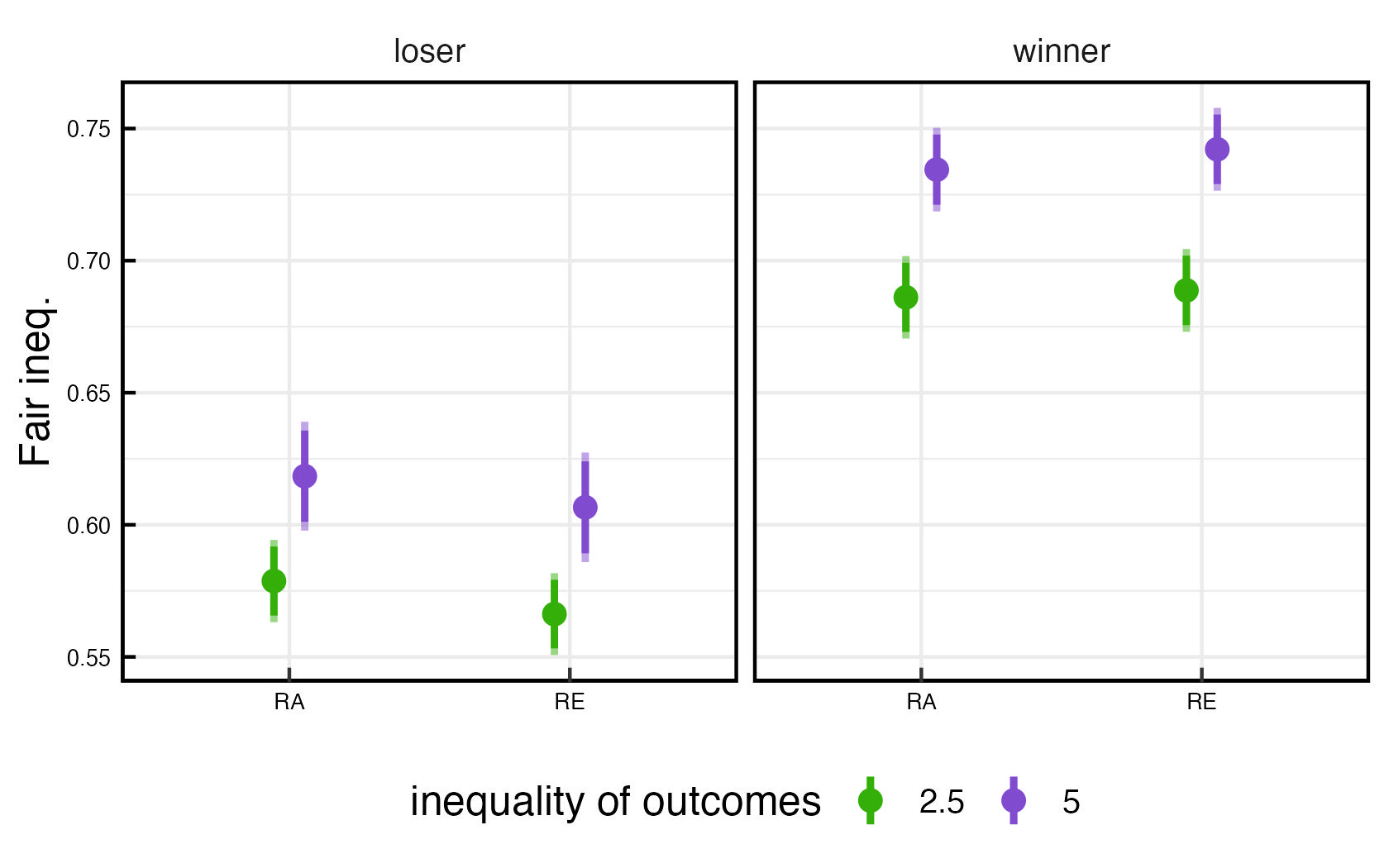

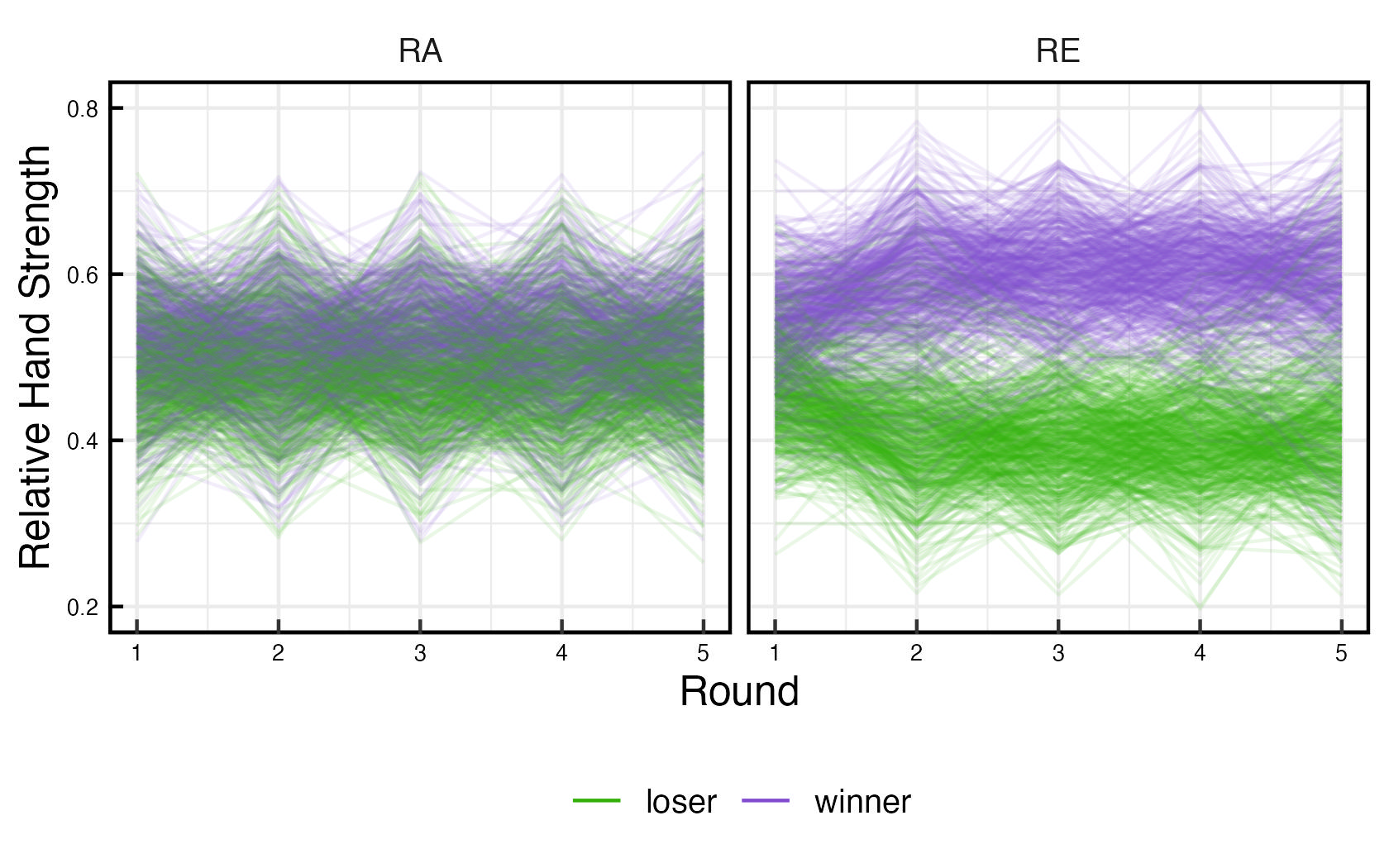

We document a dual-track process where:

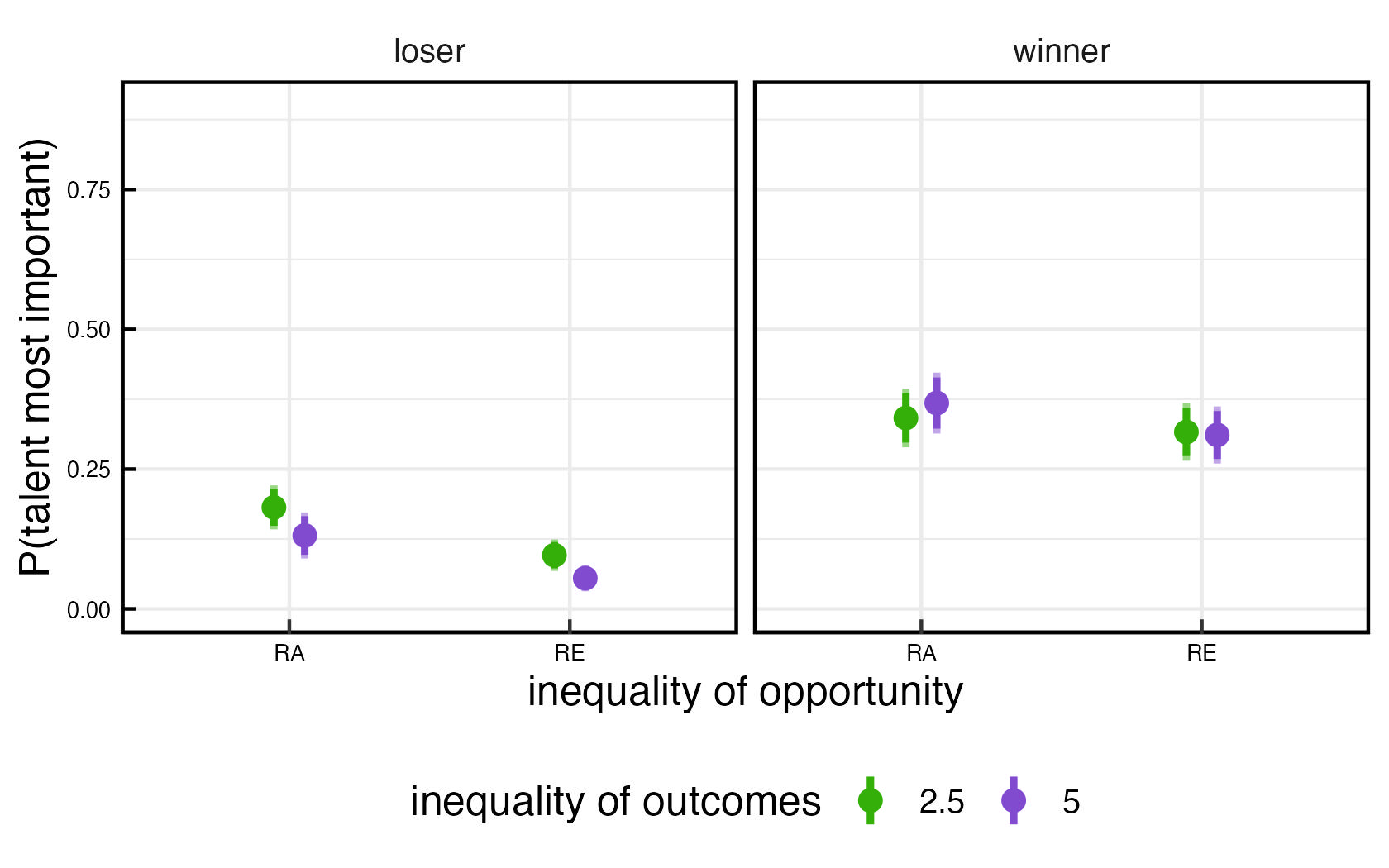

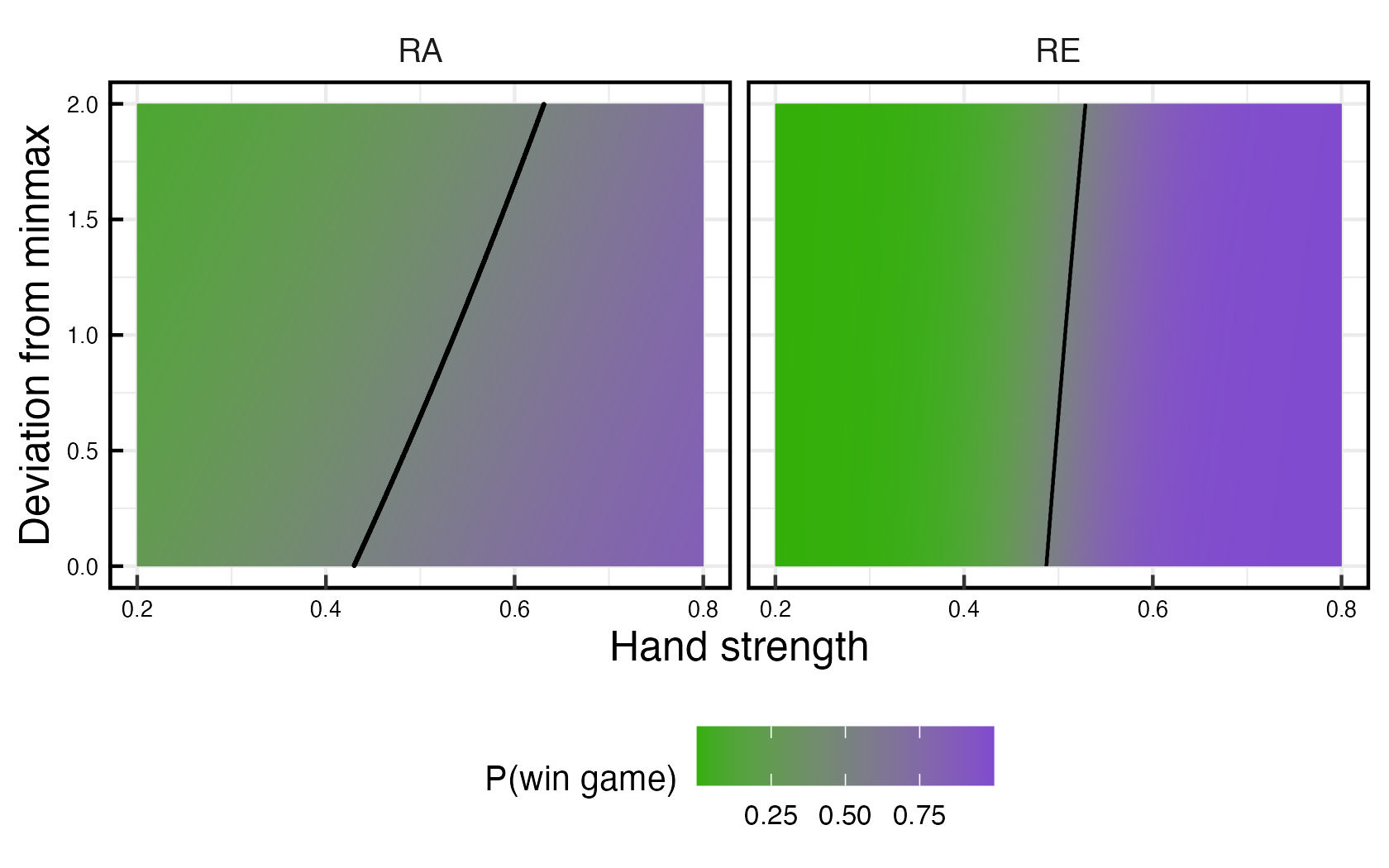

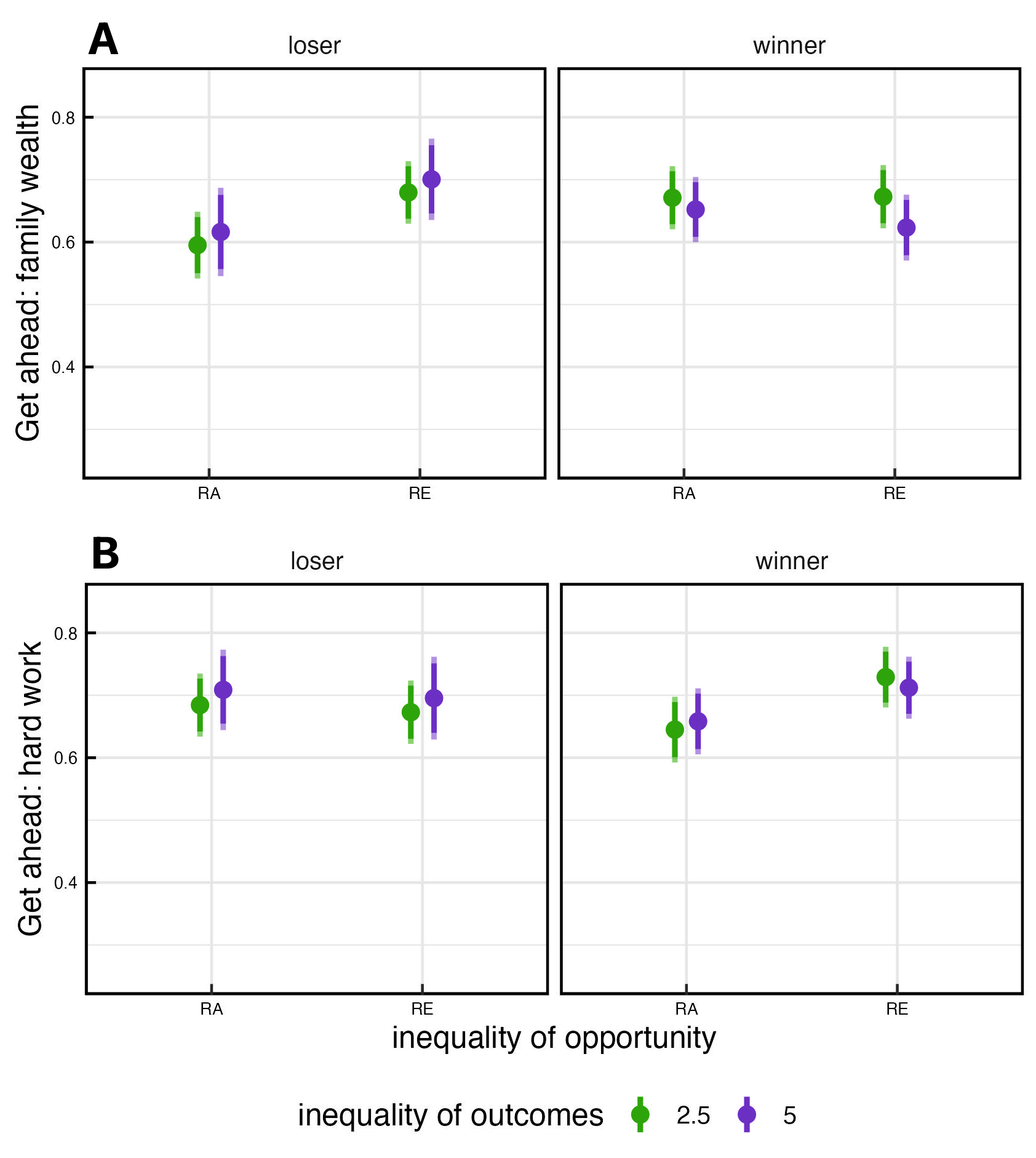

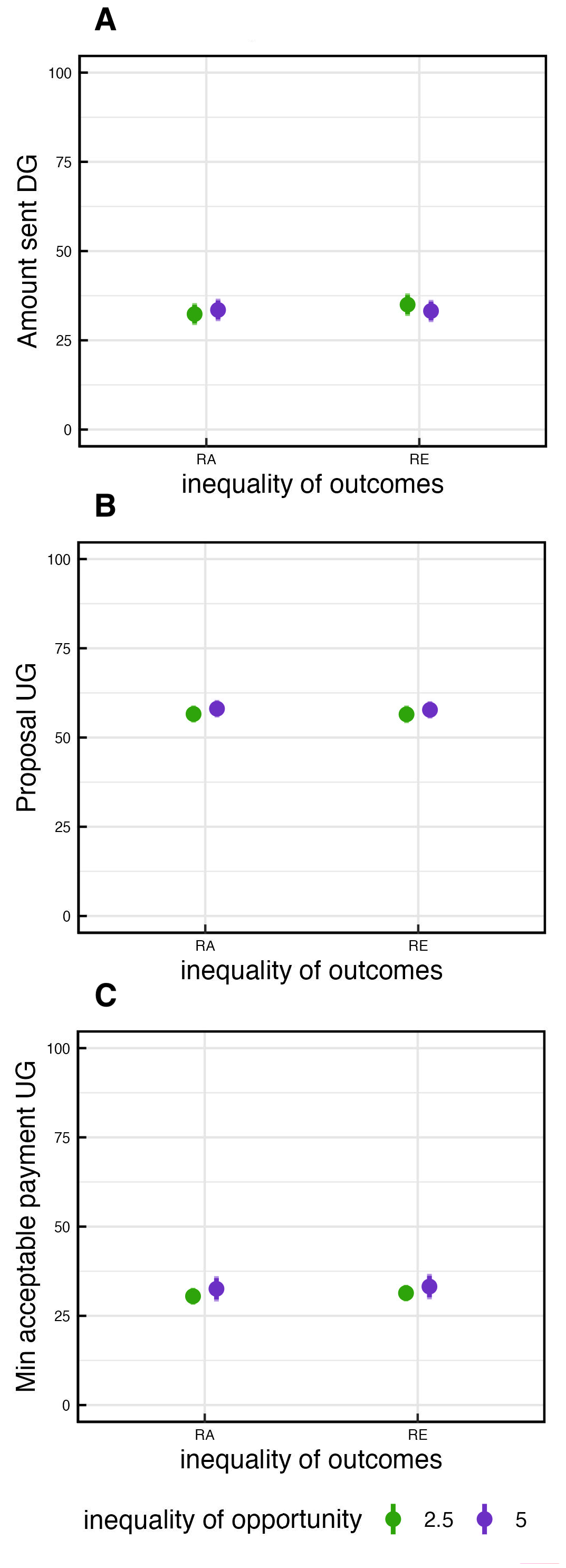

Rejection of procedural unfairness: Unequal opportunities are seen as less fair than equal opportunity, but the size of outcome inequality doesn’t affect fairness evaluations.

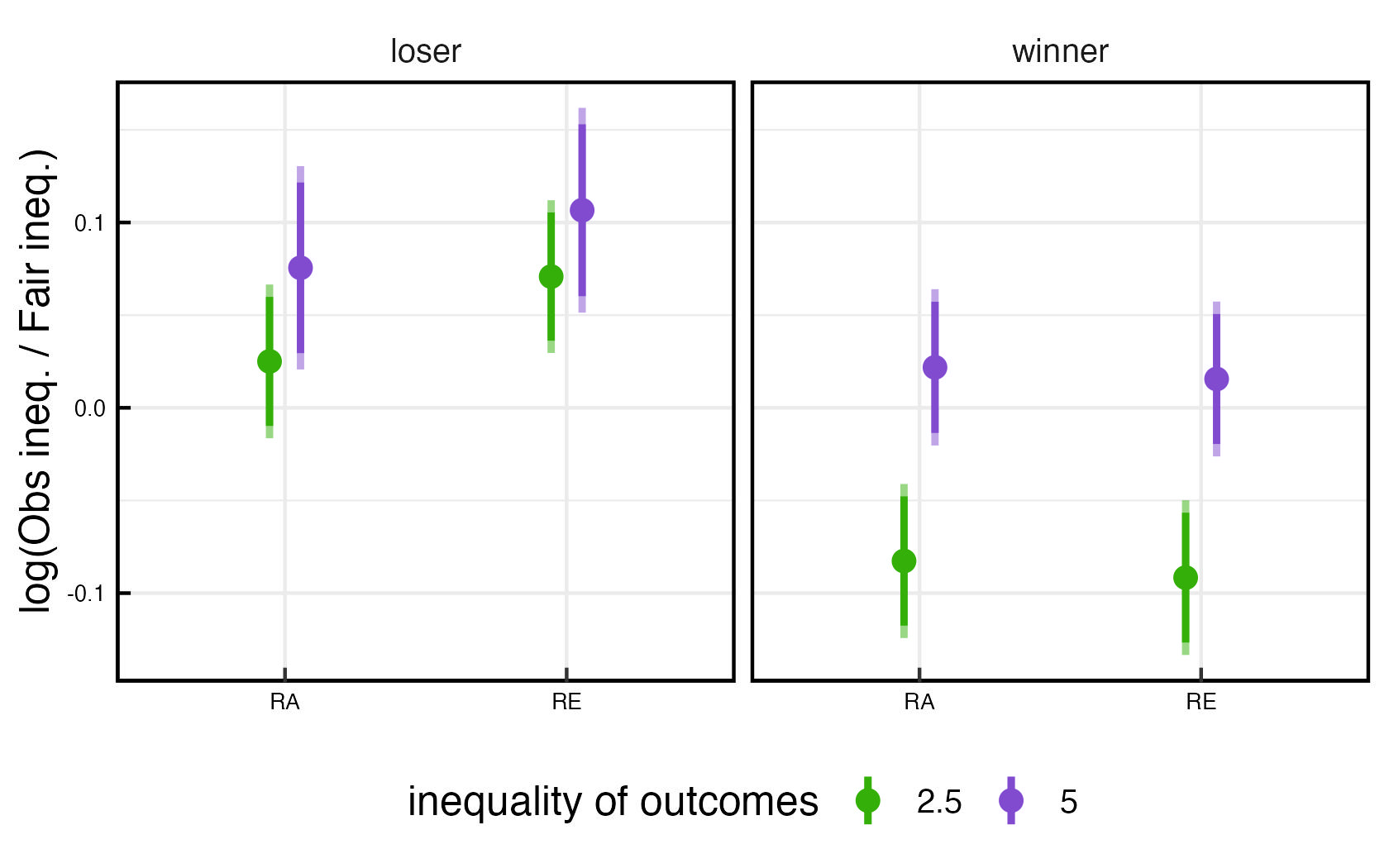

Normalization of inequality: People anchor their evaluation of outcome inequality in what they experience; opportunity distribution doesn’t affect tolerance for disparities.

Personal consequences amplify effects: Winners see more fairness, accept larger gaps, and credit talent—regardless of rules or results.